Bill 9 - Good Intentions, Misaligned Reality

A bold political gesture that risks failing Maui families, workers, and economic stability.

January 5, 2026

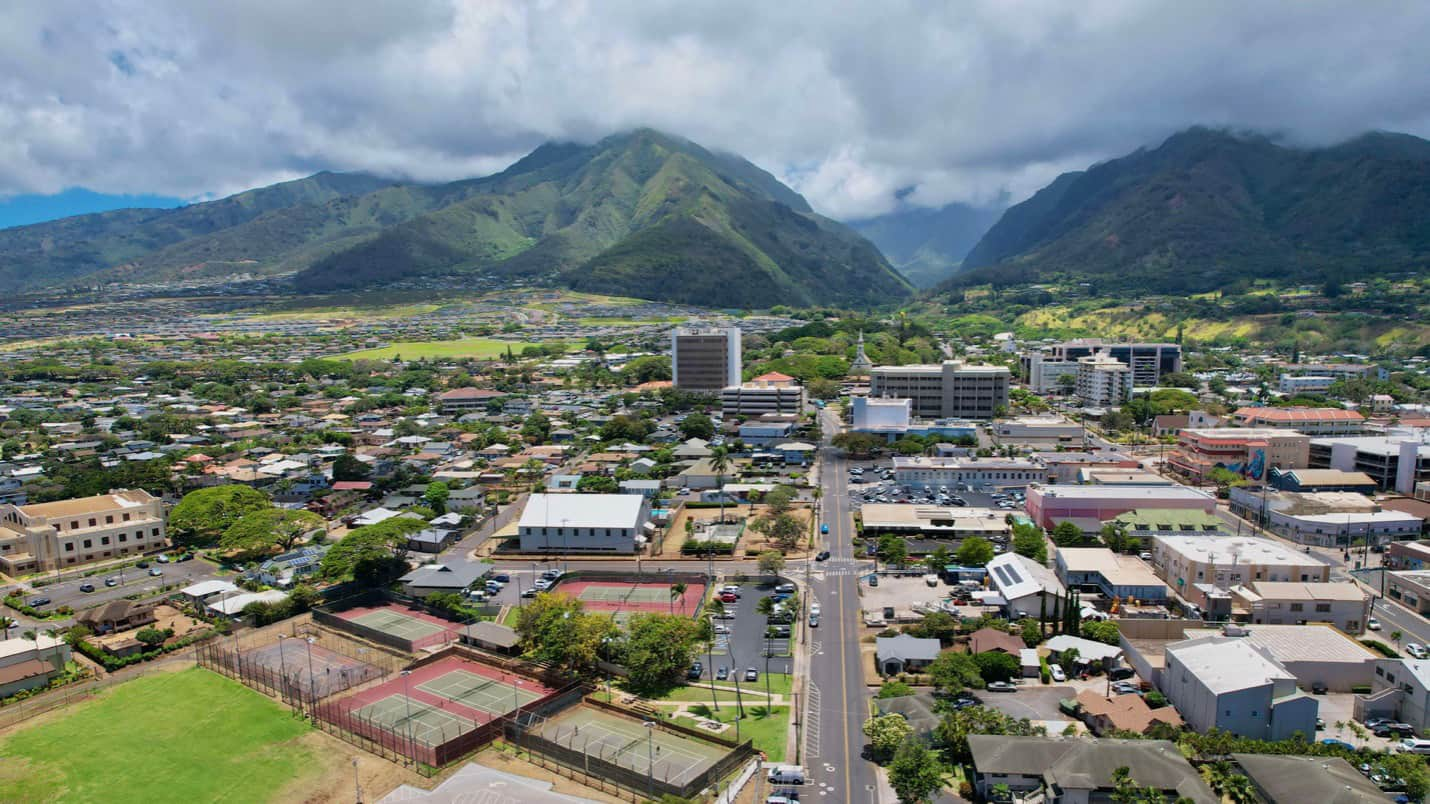

The passage of Maui’s Bill 9 emerged from real pain, urgency, and frustration. Residents have watched short-term vacation rentals occupy apartment-zoned housing while local families struggled to find stable homes. The 2023 Lahaina wildfires intensified that crisis and created a renewed moral demand to prioritize residents over visitors. Bill 9 reflects that emotion: a commitment to say “Maui first.” Its intentions are not only understandable — they are deeply human.

But public policy must ultimately succeed in practice, not merely in symbolism. And this is where Bill 9 falters.

Bill 9 rests on a central assumption: remove short-term rentals from apartment zones and those units will organically transform into homes for local families. However, much of the housing affected by Bill 9 was never intended — economically or physically — to serve as workforce housing. These units are typically high-priced, resort-style condominiums, with rents often ranging from $3,500 to $5,000 per month. To sustain that cost without financial instability, a household generally needs to earn approximately $150,000–$180,000 per year. The median Maui County household earns closer to $95,000. For most families, those rents are not merely challenging — they are fundamentally unattainable.

Even for households with the financial capacity, these units rarely align with family living. Many complexes restrict parking to a single stall. Many prohibit pets. HOA governance is strict. The physical and cultural design of these properties reflects their origins as visitor accommodations, not community neighborhoods. They do not reflect how Maui families actually live.

Compounding this, it is far from guaranteed that these units will truly enter the resident housing market. A significant number may eventually be rezoned to continue visitor use. Some owners may pursue litigation. Others may sell. Some properties may simply sit vacant. The sweeping impression that Bill 9 will automatically deliver a massive inventory of resident-ready homes is therefore uncertain at best.

A commonly repeated belief is that forcing these units out of vacation use will naturally drive rents down to resident-friendly levels. Realistically, any decline is likely to be limited, concentrated primarily in the luxury tier, and insufficient to close the affordability gap. Maui’s housing crisis is not solely a matter of unit count. It is a matter of affordability — driven by land costs, construction costs, carrying costs, insurance burdens, high HOA fees, and wages that do not match those economic realities. Even if rents soften slightly, resort condominiums are unlikely to convert into genuine workforce housing in the near term.

This is where the conversation must become more honest: how many homes does Maui actually need in the short term, based on who is truly here, working, and likely to remain over the next several years?

The widely cited “15,000 housing units needed” figure reflects long-range projections built largely on population forecasts. It does not fully capture Maui’s evolving job structure, post-fire economic conditions, or out-migration pressures. In the nearer term, when housing need is analyzed through the lens of workforce stability and disaster recovery, a more focused picture emerges.

First, wildfire survivors represent a very real and ongoing need. Approximately 12,000 residents were displaced, and many remain in temporary or precarious housing situations. While exact numbers vary by source, state housing plans consistently acknowledge that, over the next three to five years, several thousand displaced families — likely between four and six thousand households — will still require stable replacement housing until Lahaina is rebuilt.

Second, workforce stability is critical. If housing remains inaccessible, Maui risks losing nurses, teachers, police officers, hospitality workers, construction workers, and young families. Preventing that erosion requires roughly 2,000 to 3,000 additional workforce-appropriate housing units — housing built for families, with practical living conditions and attainable rents, located near employment centers.

Taken together, that suggests that Maui’s short-term, economically grounded housing need is closer to 6,500 to 9,000 functional homes, not 15,000 — and certainly not luxury vacation condos miscast as family housing. These are the homes that maintain social cohesion, protect essential services, and stabilize the community.

Bill 9 does not meaningfully address this need.

And even before its housing promises are tested, Bill 9 is already encountering another major barrier: the law has entered the courtroom. Within days of passage, the first lawsuit challenging Bill 9 was filed by Royal Kaanapali, arguing that the legislation strips long-standing, legally relied-upon property use rights and may constitute an unconstitutional taking. Plaintiffs contend that owners invested based on decades of county zoning practice and documented allowance of transient accommodations, and that retroactively eliminating those rights without compensation violates constitutional protections.

This matters for three reasons. First, litigation can delay implementation, creating years of uncertainty. Second, courts may reshape or limit the law, reducing its actual effect. Third, legal battles add cost and risk for the county and deepen instability for residents, property owners, and the broader economy. In short, Bill 9 may not only underperform its housing promise — it may also become tied up in legal conflict that prevents it from functioning as written.

Meanwhile, the bill carries significant risk. Tourism — whether people embrace it or resent it — still funds a major share of Maui’s economy. It supports employment, county revenues, local businesses, and services residents depend on. If Maui constricts its tourism infrastructure without genuinely expanding usable, affordable resident housing, the island risks losing twice: economic stability and social stability, without meaningful housing relief in return.

The deeper truth is that Maui’s crisis is structural. It is driven not merely by visitor use of housing, but by land constraints, exceptionally high building and maintenance costs, regulatory and infrastructure limits, and wages that lag behind living costs. Bill 9 does not fundamentally address these realities. Instead, it risks directing political energy toward a solution that may feel emotionally satisfying yet functionally underperforms.

In that sense, Bill 9 risks becoming an example of policy that “shoots itself in the foot”: it seeks to protect residents but may instead damage key sectors of the economy, create false expectations, deepen community division, and still fail to deliver homes that ordinary families can actually occupy. None of this dismisses the legitimacy of the anger, grief, or determination that brought Bill 9 forward. The people demanding change care deeply about Maui’s future. Their pain is real. Their desire to defend their home is honorable. But effective policy requires more than moral urgency. It requires economic clarity, honest math, realistic expectations, and alignment between intention and impact.

Bill 9 expresses heart. What Maui now needs — urgently — are solutions that deliver both heart and reality.

Explore the Coastline of Distinction

Discover Maui’s most exceptional properties, from Kapalua’s ridge-line sanctuaries to Kaanapali’s oceanfront retreats.

MARY ANNE FITCH

REALTOR® · RB-15747 · SENIOR PARTNER

GLOBAL LUXURY SPECIALIST